For Further Information Contact:

The EU AI Act – and what it means for most companies

06/03/2024Much has already been written about the “AI Act” – critics see it as a regulatory monster, the creators praise it as a beacon of global AI regulation that will promote innovation. But how does the AI Act work in practice? For whom does it actually apply – even outside the EU? And what do companies have to be prepared for? We’ll answer that in part 7 of our AI series.

First of all, the AI Act (AIA) has not yet been passed at the time of this post. After the political agreement last autumn, the proposal for the “final” text has been available since the end of January, and most recently the EU Council of Ministers approved the act on 2 February 2024 (this version can be found here). The formal adoption by the EU Parliament is currently not expected until April. Also, the current text is still a draft that still needs to be editorially cleaned up. In particular, the recitals and articles still need to be renumbered throughout (so they are not referenced here). However, major changes in content are no longer to be expected.

- Control concept

Like the GDPR, the AEOI is directly applicable EU law as a regulation. Enforcement takes place partly in the Member States (each of which must designate a market surveillance authority and an authority to regulate the procedures of the bodies for assessing product conformity), partly centralised (e.g. the EU Commission is responsible for General Purpose AI Models).

As with the GDPR, there are central institutions, e.g. the “European Artificial Intelligence Board” (EAIB), for which each member state appoints a delegate. A “Scientific Panel of Independent Experts” is also to be created. As part of the European Commission, the central “AI Office” is intended to support the market surveillance authorities, but also to provide templates and, for example, monitor copyright compliance in connection with AI models. The European Commission also has direct supervisory responsibilities.

It is not yet clear if and when the AEOI will apply not only to EU member states, but also to the EEA states. The AEOI applies to private organisations as well as public authorities. Exceptions apply to the military, defence and national security sectors, as these are still largely reserved exclusively for member states.

Although the AEOI is long (245 pages in the current draft) and – like almost every EU decree – tedious to read, it is not particularly complicated. Short:

- A distinction is made between “AI Systems” (AIS) and “General Purpose AI Models” (GPAIM).

- The personal and local scope is defined, with a distinction being made between providers of AIS and GPAIM (“providers”) and users of AIS (“deployers”).

- A few AI applications will be banned.

- Some AI applications are defined as “high risk”; they are regulated by the relevant AISs (“High-Risk AI System”, HRAIS): for an HRAIS, certain requirements must be met (e.g. quality and risk management, documentation, declaration of conformity), compliance with which must be ensured primarily by the providers; a few duties are also imposed on deployers.

- For all other AIS, some more general obligations are defined for both providers and deployers, primarily for transparency.

- In the GPAIM, a distinction is made between:

- not recorded at all (very few cases),

- “normal” (with minimal obligations for the providers) and

- “systemic risks” (with additional obligations for providers).

- The European Commission maintains a central register of HRAIS and there are various regulations (including reporting obligations) in place to monitor and respond to HRAIS-related incidents.

- Various national and EU-wide authorities are involved in enforcement. The result is a complicated web of responsibilities and voting procedures.

- Accompanying instruments are foreseen, such as:

- “regulatory sandboxes”: (right to involve supervisory authorities in the development of new AIS for early legal certainty),

- Regulations for testing AIS in the “real world”,

- Codes of Conduct and

- various provisions for the creation of standards, benchmarks and templates. How relevant they will really be in practice remains to be seen.

- There are some provisions on enforcement, the powers of investigation and intervention by the supervisory authorities, administrative fines (usually slightly lower than under the GDPR) and a right of access for people in the EU about whom decisions have been made with the help of AI.

- Provisions on entry into force and very few transitional provisions.

GPAIM are noticeably milder and less regulated than AIS, and are also dealt with separately, due, among other things, to the fact that they were only included as a regulatory object in the course of the consultations; the original draft of the AEOI dates back to mid-2021, i.e. before the hype around ChatGPT & Co. and the “Large Language Models” (LLMs) on which these applications are based. The GPT LLM is a classic example of a GPAIM.

The AEOI is primarily a market access and product regulation, as we know it for various products with increased risks (e.g. medtech). It distinguishes the AEOI from the GDPR, which primarily regulates conduct (processing of personal data) and the rights of data subjects. While there are a few general principles of conduct for the use of AI and a data subject right, they are selectively geared towards specific use cases; even the “forbidden” AI applications are basically very narrowly defined. In particular, it regulates the accompanying measures to be taken for AIs that are considered to be particularly high-risk, and regulates how they must be placed on the market, deployed and monitored.

Some HRAIS will be AIS, which are part of already regulated products, in which cases many of the obligations provided for by the AEOI already apply in a similar way; the AEOI also regularly refers to these and sees a combined implementation (e.g. with regard to risk and quality management, documentation and declarations of conformity, but also with regard to official supervision). Obviously, the legislature was anxious not to let the bureaucracy get too out of hand; Whether he has succeeded in this, however, seems questionable to many. After all, it is consistently evident that a risk-based approach should apply. Many of the specifications are rather generic, which means that there is room for manoeuvre in implementation in practice.

The AEOI repeatedly states that it applies in addition to the existing law, i.e. that it does not intend to restrict it in any way. This applies in particular to the GDPR. The AEOI also does not in itself constitute a legal basis for the processing of personal data, with a few exceptions – namely the case in which it is essential (meaningful is not sufficient) to process special categories of personal data for tests of HRAIS (but not other AIS) with regard to possible bias. On the merits of the case, it contains hardly any provisions in the area of data protection; however, it is striking that with the EU Data Protection Supervisor, a data protection authority is to be given the task of AI market surveillance over the EU institutions. It remains to be seen to what extent EU member states will also entrust AI market surveillance to their existing data protection authorities.

What is also striking is that the legislator apparently had some difficulty regulating the state use of AIS in the area of law enforcement and especially in systems for biometric remote identification of people in public (e.g. based on their face or walk via cameras in public). The use of these systems is permitted in certain cases and is regulated in much more detail in the AEOI than any other application (it should be noted that the area of safeguarding national security is excluded from the scope of the AEOI from the outset). For companies, this will be less relevant. That’s why we won’t go into detail about these and other government applications here.

- Scope: What is an AI system?

Unfortunately, the scope of the AEOI is far from clear in several respects – and it is extremely broadly defined.

This starts with the definition of AIS. It contains five elements, three of which apply to almost every IT application, namely, in simple terms: that a system is (i) machine-based, (ii) an input is derived from how an output should be generated, and (iii) that this output can do something outside the application. This probably applies to any classic spreadsheet or image editing software, as they also generate an output from input (numbers and formulas, images) (result of the calculations, images processed with filters) and these can make a difference.

In addition, there are other criteria: that (iv) the system can adapt even after its implementation (there is talk of “may” – so the ability of a system to learn is not a mandatory criterion). And that the system (v) is designed in such a way that it behaves more or less autonomously. This last element of the definition, i.e. partial autonomy, thus appears to be the only really relevant distinguishing feature that distinguishes AI systems from all other systems. However, it is also not entirely clear what “autonomy” means. In essence, it is probably intended to differentiate from systems whose output is generated entirely according to rules formulated by humans, i.e. a completely (i.e. statically or deterministically) programmed system (“if-then systems”) – in contrast to systems that, for example, operate pattern recognition on the basis of training. It is no longer static or deterministic programming that alone determines which output results from which input. The considerations are also expressed in this direction. While most people think of deterministic code as that of human programmers, it can also be programmed by an AI. A system programmed deterministically by an AI is therefore not an AIS because it lacks autonomy. This leads to the exciting question of how the regulations of the AEOI could be circumvented in this way, e.g. by commissioning an AIS to develop a system based on its knowledge that has deterministic programming, but is still so complex that we humans no longer understand its function or decision-making logic. For the time being, however, we will have to assume that the applicability of the AEOI can be prevented by using only systems that do not act autonomously, even if they lead to the same result or do equally problematic things as an AIS.

GPAIM’s definition is even more diffuse than AIS’s. What an “AI model” is, is not even said. A “general purpose” (or on German “general purpose”) AI model becomes one when it can be used for many different tasks and is brought to market in this general form so that it can be integrated into a variety of systems and applications.

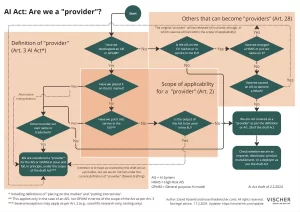

- Scope: Who is considered a provider?

As already mentioned, the two most important roles that an organization can have separately or simultaneously under the AEOI are those of the provider and those of the deployer. While there are other roles such as those of importers, distributors and product manufacturers, as well as the EU representative, they can ultimately be attributed to the provider. Regulators can take action against anyone, and everyone must cooperate with them.

It is crucial that a company identifies its role in this regard for each AIS or GPAIM it deals with, as it is from this role that the obligations under the AEOI arise. Most of the obligations are imposed on the provider (see below).

Provider is primarily the person who (i) develops an AIS or GPAIM (by himself or on behalf of him), and (ii) puts it on the market or in use under his or her name:

- By definition, ‘placing on the market’ refers only to the EU market and covers only the first placing on the market.

- “putting into service” also refers only to the territory of the EU. This refers to the initial provision of the AIS to a deployer, but also to the own use (this variant does not apply to GPAIM, as they are only a preliminary stage of an AIS according to the concept of the AEOI).

- In both cases, an orientation towards the EU is presumably meant, i.e. it must be the goal; A “non-intentional spill-over” is not enough.

- It does not matter whether this is done for a fee or free of charge.

Before this happens, research, development and testing on and from AIS are excluded from the scope of the AEOI (the only counter-exception is “field trials”, i.e. testing in the “real world”; there is a separate chapter in the AEOI for them).

This definition has consequences. In any case, according to the wording, anyone who does not place an AIS developed by him on the market in the EU and does not deliver it for his own or third-party use there cannot be a provider and is therefore not subject to the AEOI, even if his AIS finds its way there or has an effect there. This is true even for companies located in the EU. This seems clear on the basis of the wording of the definitions, but it creates a gap because the territorial scope itself has been broadened: according to this, those providers who are located abroad should also be covered, provided that the output of the AIS is used in the EU as intended. This provision is intended to prevent the circumvention of the AEOI by AIS operated and operated abroad with EU effect, but according to the wording, it does not apply to providers because the legal definition of the provider already requires an EU market reference. It will be interesting to see how regulators will deal with this legislative oversight, as while the legislator’s intent is clear, so is the wording.

Either way, however, there is a scope of application for the above regulation: Exceptionally, anyone who assumes the role of a provider is also considered a provider. This refers to those who (i) affix their name or trademark to an HRAIS (whatever that means) that is already on the EU market, (ii) substantially change such HRAIS (but it is still an HRAIS), or (iii) modify or use an AIS on the EU market in such a way as to become an HRAIS, contrary to its original purpose. One example is using a general-purpose chatbot for a high-risk application. The original provider is then no longer considered as such. In this case, the special regulation will cover such providers if they are based outside the EU, but the output of the AI is used in the EU as intended. If this is not the case, the question arises as to whether these “derivative” providers still fall within the scope of the AEOI if they themselves have not brought the AIS to the EU market and have not used it there. That would be another gap in the AEOI.

In the literature, it has been argued in some quarters that the AEOI regulates any AIS that affects persons in the EU, directly or indirectly. That is not the case, according to the view taken in the present case. It is true that the AEOI explicitly applies to all affected persons in the EU. However, this does not automatically mean that it applies to all providers, deployers and other people; their personal and territorial scope is defined separately by the AEOI. If every AIS (including its providers, deployers and other involved bodies) were automatically within the scope of the AEOI, the differentiated rules discussed above would not have been necessary at all. Rather, the inclusion of data subjects in the scope of the AEOI is necessary in order for them to be able to assert their (few) rights under the AEOI.

Only for HRAIS and only rudimentarily are the cases in which an AIS originates from several places or if the AIS of one provider contains an AIS of another provider. In these cases, a contract is to be concluded with the subcontractor that enables its customer as a provider to comply with the AEOI; the subcontractor will presumably be independently registered in accordance with its own market activities. Anyone who installs an AIS in another product, which he then offers under his own name in the EU market or places on the EU market, is considered a “product manufacturer” under the AEOI and – if it is an HRAIS (e.g. because it assumes a security function of a regulated product) – as its provider within the meaning of the AEOI. In other words, the provider can not only be the one who (i) develops an AIS first, but also (ii) the one who develops it further and incorporates it into a higher-level AIS or other product, and (iii) who presents itself according to (i) or (ii).

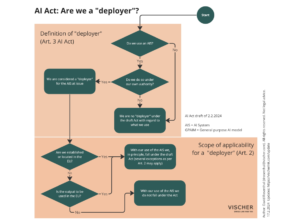

- Scope: Who is considered a deployer?

Users of AIS are registered as deployers under the AEOI and are subject to a few obligations (see below). A deployer is anyone who uses an AIS under his or her supervision. Exceptions are those persons who use an AIS only for personal, not professional purposes (although here too the drafting of the law was careless – the exception exists on two levels, but is (at least still) slightly differently formulated).

The criterion “under its authority” distinguishes the mere enjoyment of an AIS or its output from the use of an AIS as a tool in its own right. A certain amount of control will be required here in order for the criterion to be met. If a user uses a customer service chatbot on a website, they don’t have that control; In any case, this is not the intention. They can ask questions and the company controls how the chatbot answers them. It would only be different if the user succeeds in “hacking” the chatbot and causing it to make unplanned statements. If, on the other hand, a company provides its customers with AI functionality as part of a service, which they should and can control within certain limits with regard to their use, then the criterion “under its authority” is likely to be met. If a company like OpenAI offers the chatbot “ChatGPT” to its customers, it differs from the customer service chatbot mentioned above in that it is OpenAI’s customer who is supposed to give the chatbot the instructions on what to talk about – and no longer the company that operates it. Of course, it is not yet clear where exactly the boundary runs (e.g. in the case of topic-specific chatbots).

The territorial scope covers all deployers who are either in the EU (whether with an establishment or because they are there as natural persons) or, if not, as soon as the output of the AIS they operate is “used” in the EU. According to the recitals, the latter rule is intended to prevent circumvention of the AEOI by providers in third countries (such as Switzerland or the USA), who collect or receive data from the EU, process them with AIS in other EU countries and send the result back to the EU for use, without the AIS being placed on the market or used in the EU. The example itself raises questions, since a company based in the EU, which asks a company in another EU country to process data with an AIS on its behalf, will probably still be considered its deployer, just as in data protection the actions of the processor are attributed to the controller. The exemption is likely to be much more relevant for those companies that are located in other EU countries (e.g. in Switzerland or the USA) and use AIS for themselves. Either way, the scheme is intended to protect natural persons affected by the use of the AIS on the territory of the EU. According to the recitals, it is necessary that the use of AI output in the EU was intentional and not merely accidental.

What exactly counts as the “use” of AI output in the EU is not elaborated. It is conceivable whether it is sufficient for AI output generated in other EU countries to have an effect on people in the EU, but in our opinion it is rather questionable. Some examples:

- Anyone who publishes AI-generated content on their website in other EU countries and (also) targets it to an audience in the EU is likely to be covered.

- The company that sends texts generated by an AIS to its customers in the EU area is also likely to be covered.

- If a document created by an AIS in another EU country happens to find its way into the EU, then the AIS deployer is not yet registered.

- The use of an HRAIS or the implementation of a practice prohibited by the AEOI by a Swiss employer in relation to its Swiss employees should not be subject to the AEOI even if it employs employees from the EU but only uses the output of the AI at the company’s headquarters in Switzerland.

- However, if the employer uses a cloud in the EU for this purpose, the legal situation may be different: It is still unclear whether outsourcing the operation of an AIS to a provider based or data center in the EU means that the output of the AIS is also considered to be “used” there. We believe that this is not the case: in view of the primary protection purpose, namely the protection of the health, safety and fundamental rights of natural persons in the EU, outsourcing IT operations to the EU may not be sufficient in itself. There is no connection between the place of processing or the provider and the data subjects. A branch office is certainly not justified by the mere commissioning of a service provider in the EU (as is not the case under the GDPR). The secondary protection objectives of the AEOI also include the protection of democracy, the legal system and the environment, but even these do not really justify an extension of the scope; it would still be most likely to be considered for AI in terms of the protection objective of environmental protection with regard to the energy consumption of data centers, but the AEOI itself does not contain any really relevant rules in this regard.

Notwithstanding the remaining ambiguities, the regulation on the use of AI output in the EU leads to a significant extraterritorial effect of the AEOI. This means that many Swiss companies should also deal with the labelling obligations imposed by the AEOI on deployers. On the other hand, as mentioned above, with regard to a possible role as a provider, they can take the view that they are not covered if they do not place the AIS on the market or use it in the EU.

- Further delimitation issues for companies

The role definitions of the AEOI raise further questions of demarcation, in particular where companies develop AIS themselves, use it in dealings with third parties or pass it on within a group of companies.

It is unclear what counts as “developing” an AIS. Is this already the case, for example, if a company parameterizes a commercial AI product for its own application (e.g. equips it with appropriate system prompts), fine-tunes the model or integrates it into another application (e.g. integrating chatbot software offered on the market into its own website or app)? If this were the case, many users would become providers themselves, as the legal definition of the provider also covers those who use AIS for their own use, if this use is intended in the EU and under their own name. According to the view expressed here, such a broad understanding is to be rejected, but it is to be feared that the supervisory authorities will show a broad understanding here and regard at least those actions as development that go beyond prompting, parameterization and the provision of other input. Accordingly, a fine-tuning of the model of an AIS would be covered, but the use of “Retrieval Augmented Generation” (RAG) would not. It would also be conceivable to adopt an approach based on the risk posed by the contribution in the individual case, which, however, would lead to considerable legal uncertainty, because the same act would lead to a different qualification of the person carrying it out depending on the purpose of the system. It should be taken into account that the deployer also remains obliged to a certain extent.

Until the legal situation has been clarified, it is recommended as a precautionary measure for companies to also indicate the name of the technology supplier to the outside world when using such AIS (e.g. “Powered by …” in the case of a chatbot that is offered as a service to its own customers on the website). Thus, it can be argued that the AIS – even if the implementation or optimisation were to be considered a development – is not considered to be used under its own name or trademark (“under its own name or trademark”). Another possible precautionary measure is to restrict the permitted use of an AIS to persons outside the EU, because the legal definition of the provider will presumably no longer apply.

It is also unclear how the transfer of AI services or AI technology within a group of companies is to be evaluated. Various delicate scenarios are conceivable here. One scenario is the case in which group company X outside the EU buys an AIS from provider Y outside the EU and then makes it available to the other group companies in the EU as well. If the AIS has not yet been introduced on the EU market or put into use in the EU, X can become its “distributor” or even “importer” even without having developed it further. This would entail a number of special obligations. While X can probably prevent qualification as an importer (and provider) by only passing on AIS to the EU that are already on the market there, this does not protect X from qualifying as a distributor. In the present case, it can at least be argued that the term presupposes that the undertaking is part of Y’s ‘supply chain’ referred to in the definition and that it no longer reasonably includes intra-group distribution of an AIS to group companies of X. They also don’t make the AIS publicly available like a distributor does.

In the corporate context, the question can also arise as to at what point a company that makes a product with AI-supported functionality available to its customers is itself considered a provider and the customers are considered its deployer. The hurdles are not very high: Let’s take as an example a bank outside the EU that offers its EU business customers an AI-supported analysis of their portfolios in its online banking and trading; this is part of the bank’s commercial service. The Bank, if it has developed this functionality itself or has had it developed, will already be considered a provider on the basis of its own use, especially since it uses it in the EU and does so under its own name.

The customers who use the AI analytics feature can themselves become deployers and be subject to the AEOI, even if the bank does not take care of it. There are two requirements to consider: Firstly, the customers must be located in the EU or the output of the AI analysis must be used in the EU. Second, they must use the AI function under their supervision (“under its authority”) (see above). If the bank customer thus gains the necessary control over the AI function, he (who, as a business customer, does not fall under the exception for personal, non-professional uses) will have to and want to ensure on his own responsibility that it is not a prohibited AI practice and that any applicable deployer obligations are complied with. The difficulty in practice can be that it may not be clear to EU deployers, especially in the case of providers from other EU countries, where and when AIS are used in the products and services used and what exactly they do.

In this context, the question may also arise as to whether a provider can only logically occur if there is also a deployer to whom the provider makes the AIS available. The answer to this is likely to be a “no”. Otherwise, all providers who offer AI services only to consumers in the EU would not be covered by the AEOI, because such users are not considered deployers by virtue of an exemption. The definition of a provider does not require a deployer: on the one hand, it is sufficient to make it available for use for own purposes in the EU (“for own use in the Union”); in order to fulfil this, it will probably be sufficient for the provider to address users in the EU and allow them to use the service there, as it is still the provider’s service and thus “his” use of the AIS. On the other hand, the alternative criterion to the provider qualification “making available on the market” allows it to be sufficient that an AIS “for … use on the Union market in the course of a commercial activity’. That seems to be the case here. However, this question has not been conclusively clarified either.

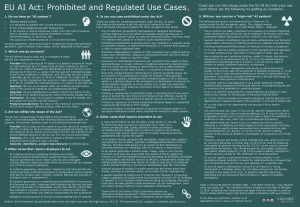

- Prohibited AI Applications

Eight specific “AI practices” are banned altogether under the AEOI. In most cases, the ban applies both to those who place the AIS in question on the EU market or for the first time in the EU, and to those who intend to use an AIS in this way (which, as shown, also includes those who use it abroad, provided that the output of the AIS is also used in the EU as intended).

The list of prohibited AI practices is very specific:

- Use of subliminal, intentionally manipulative or deceptive techniques that aim or have the effect of materially distorting behaviour or impairing the person’s ability to make an informed decision, if it may result in a decision that causes or may cause significant harm

- Exploiting people’s weaknesses due to their age, disability, or particular social or economic situation in order to influence their behavior in a way that causes or may cause significant harm

- Biometric classification to draw conclusions about an individual’s race, political opinions, trade union membership, religious or philosophical beliefs, sex life or sexual orientation (i.e. based on biometric data)

- Rating or classifying individuals over a period of time on the basis of their social behavior or known, inferred or predicted personality traits, if that social assessment results in adverse or unfavorable treatment that is unrelated to the context of the data or that is unjustified or disproportionate

- Biometric identification remotely and in real time in publicly accessible spaces for the purpose of law enforcement, with the exception of targeted search for victims, prevention of specific threats in the event of significant and imminent threats, or locating or identifying suspects of certain defined categories of crimes, subject to additional conditions (e.g. court approval, permission only for the search for specific targets)

- profiling or assessing personality traits or characteristics of individuals in order to assess or predict the risk of committing crimes, except to support the risk assessment of individuals involved in a crime

- Building or expanding a facial recognition database based on untargeted scraping on the internet or CCTV footage

- Infering people’s emotions (including intentions) in the workplace or educational setting, except for medical or safety reasons

It should be noted that these practices are only prohibited if they are carried out by means of an AIS. For example, anyone who carries out emotion recognition in the workplace solely on the basis of if-then rules programmed by themselves, i.e. by human hands (no pattern recognition), is not covered. In addition, the facts are often formulated very specifically, so that exceptions quickly arise. The use of AIS to convict students cheating on an exam is not covered by the ban on recognizing emotions and intentions (although it is a high-risk application).

So, for example, if you use an AIS to carry out “Data Loss Prevention” (DLP), you are not engaging in a prohibited practice, even though the theft of data can be a criminal offence and DLP therefore also includes the assessment of the risk of a crime in the broadest sense, but this is not the goal, but the prevention of an unwanted data leak, no matter whether it is a criminal offence (the prohibited practice no. 6 above is aimed at “predictive policing”, and not at the prevention of offences that are in progress).

Another example: In the case of Prohibited Practice No. 1, it is not enough for people to be manipulated using AI. This must also be done for the purpose of substantially influencing their behaviour, preventing them from making informed decisions, and this must also lead to a decision that may cause substantial harm to the person. Thus, even the considerations state that the “usual and legitimate commercial practices” in the field of advertising, which are also lawful in other respects, are not covered here. The case is somewhat less clear in the case of practice No. 4 (scoring), which can be understood quite broadly because it only presupposes disadvantageous treatment. However, the prohibition only applies if the data have nothing to do with the treatment in question or if the less favourable treatment is disproportionate or unjustified. It will be interesting to see whether, for example, AI-supported functions that calculate the optimal price for each visitor to an online shop based on his or her behavior from the provider’s point of view will be covered. In order to counteract the ban, a system would have to be used here as well, which does not judge autonomously, but acts according to clearly predefined rules.

In the case of Practice No. 4, the question will continue to arise as to whether and when it means AI-based credit assessments and would thus prohibit them. A person’s ability to pay is neither a social behavior nor a personal characteristic, but the willingness to pay can be. In other words, it would cover anyone who places an AIS on the market that shows correlations between a person’s behaviour and his or her presumed unwillingness to pay for the purpose of granting credit, using data from a context that has nothing to do with the person’s willingness to pay or that would be disproportionate or unjustified. The provider would counter this with a solution for a creditworthiness scoring that it also covers solvency. To this it could be replied that the assessment “Is more likely not to pay his bills” can certainly be understood as a “social score”. In this case, in order to use the AIS, it would have to be shown that only data collected in the context of paying invoices is used and that the creditworthiness assessment actually makes the right ones to some extent and that the consequences are justifiable. Of course, such an application would be covered by HRAIS in one way or another (see below).

- High-risk AI systems

There are two types of AIS that are considered a “high-risk AI system” (HRAIS). First of all, in principle, they are all those AISs that are a product according to EU law, for which a conformity assessment by a third party is required before distribution or use, or are used as a safety component in these (those AIS, the failure of which leads to a risk to the health or safety of people or property, are also considered to be safety components). The relevant EU law is listed in an annex to the AEOI. In these cases, the requirements of the AEOI supplement the rules that apply to these products anyway.

Furthermore, all those AISs that are listed in a further appendix to the AEOI are considered to be HRAIS. As with the prohibited practices, these AIs are very specifically defined, which is why the list should be regularly reviewed and, if necessary, adjusted. Currently, the list includes the following applications. The decisive factor in each case is whether an AIS is to be used for the purpose in question. In the relevant annex, the areas of application are usually defined, and then the individual cases of high risk covered are described in more detail:

- Remote biometricidentification using AI that goes beyond mere authentication and biometric categorization, using or deriving sensitive or proprietary features

- Recognition of emotions or intentions based on biometric data using AI

- AI is to be used as a safety component in the management and operation of critical infrastructures, in road traffic, or in the supply of water, gas, etc

- Use in education and training, where (i) AI is intended to determine access, admission or allocation to education, (ii) AI is intended to assess people’s learning outcomes or educational attainment, or (iii) AI is to be used to monitor or detect prohibited conduct in examinations

- Employment and employee use to the extent that (i) AI is used to recruit or select individuals, or (ii) AI is used to make decisions that affect employment conditions (e.g., decisions on promotions or termination of employment), evaluate performance, or assign work based on behavior or other personal characteristics

- AI is used to assess (for or as a public authority) whether essential public support and services, including health care, are or will continue to be available to a particular individual

- AI will be used to assess a person’s creditworthiness or determine their credit score, except for detecting financial fraud

- AI is used to assess and classify emergency calls from people, or to assign or triage emergency calls or emergency services or medical care

- AI is used for risk assessments and the pricingof life or health insurance

- Use for law enforcement purposes if (i) AI is to be used to assess a person’s risk of becoming a victim of a crime, (ii) AI is to be used as a lie detector or similar tool, or (iii) AI is to be used to establish the reliability of evidence (in each case, with the exception of the prohibited practices set forth above)

- Use for law enforcement purposes where (i) AI is used to assess a person’s risk of committing or committing a new offence not only on the basis of an (automated) profile, (ii) AI is used to assess personality traits, characteristics or previous criminal behaviour of a person, or (iii) AI is intended to be used to create profiles of individuals in the context of the detection, investigation or prosecution of criminal offences

- In the field of migration, asylum and border control, to the extent that (i) AI is to be used as a lie detector or similar tool, (ii) AI is to be used to assess the risk of persons entering the EU, (iii) AI is to be used to examine applications for asylum, visas, residence permits and related complaints, as well as to assess related evidence, (iv) AI is intended to be used to track, recognize, or identify individuals, except for the verification of travel documents

- AI is used by or on behalf of a judicial authority or as part of an alternative dispute resolution to assist the judicial authority in researching and interpreting facts and laws and applying them to a specific case

- AI is used to influence the outcome of an election or vote, but not when people are not directly exposed to the outcome of the AI (e.g., AI systems used to organize, optimize, and structure the administration or logistics of political campaigns)

In the practice of private companies, cases 2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 8 and 9 will be of particular relevance.

The following one-pager provides an overview of these and the other use cases and definitions of the AEOI discussed so far:

If such an HRAIS exists, the provider in particular has a whole series of tasks to fulfil, as it is primarily responsible for ensuring that the requirements of Chapter 2 of the regulations on the HRAIS are fulfilled in relation to them. These requirements for HRAIS are:

- In-depth risk management must be carried out, i.e. in particular risk assessments that are repeated over the entire life cycle of the HRAIS, with appropriate tests of the HRAIS and measures to control the identified risks (cf. our tool GAIRA);

- The data used for training, verification and testing must meet certain quality criteria;

- Detailed technical documentation for the HRAIS must be prepared and updated;

- The HRAIS must automatically log what it does appropriately in logs so that its correct functioning can be monitored over time;

- The HRAIS must be designed and supplied with instructions for use in such a way that its users can handle it correctly, understand and assess its output correctly, and be monitored and controlled by humans;

- The HRAIS must be reasonably accurate and reliable (with the European Commission encouraging the development of such standards) and it must be reasonably fault-tolerant;

- The HRAIS must have adequate security, especially to protect it against attacks from third parties, both in the field of classic information security and AI-specific attacks.

To demonstrate compliance with these requirements, providers must:

- Maintain appropriate documentation;

- Have a quality management system;

- Keep the logs generated by their HRAIS in the field (if they have them);

- register the HRAIS in an EU database (except for those used in the context of critical infrastructure);

- Have a conformity assessment carried out by an appropriate third party;

- Stamp the HRAIS with a mark of conformity (“CE”) and their contact details; and

- Notify regulators if an HRAIS poses a risk to the health, safety or fundamental rights of data subjects, or if a serious incident occurs.

A provider that is not itself based in the EU but offers an HRAIS there must designate a representative in the EU who has the necessary documentation for the EU authorities to access it. Interestingly, he is independently obliged to resign from the mandate and to inform the supervisory authority if he has reason to believe that the provider is not fulfilling its obligations under the AEOI. Importers and distributors of HRAIS also have certain obligations.

Even those who “only” use an HRAIS, i.e. the deployers, have obligations under the AEOI. In particular, you must ensure that:

- The HRAIS is used in accordance with the instructions for use;

- The HRAIS is supervised by qualified people;

- The logs that the HRAIS automatically generates are kept for at least six months;

- Any input for which HRAIS is appropriate and representative in terms of purpose;

- The provider informs about the operation of the HRAIS as part of its post-market monitoring system;

- the supervisory authority and the provider (and, where applicable, its distributor) are informed if there is reason to believe that an HRAIS poses a risk to the health, safety or fundamental rights of data subjects;

- When using HRAIS in the workplace, the affected employees are aware of it; and

- Data subjects are informed when an HRAIS is used for decisions affecting them, even if the HRAIS is only used as a support (this goes further than under the GDPR).

These obligations are not exhaustive. In a kind of general clause, the AEOI gives the market surveillance authority the power to order further measures if this is necessary to protect the health or safety of persons, their fundamental rights or other public interests, even in the case of HRAIS that are used in accordance with the law.

Furthermore, analogous to the GDPR, the AEOI provides for a kind of right of access for data subjects in the EU (but not Switzerland) if a deployer makes a decision based on the output of an HRAIS that has legal or comparably significant effects on the person that are detrimental to his or her health, safety or fundamental rights. It can then demand that the deployer explain to it what role the HRAIS played in the decision and what the essential elements of the decision were. This applies to all HRAIS of the 15 categories listed above, with the exception of No. 2. Claims in accordance with the GDPR are reserved; they are narrower in that they relate to fully automated decision-making.

Due to the extraterritorial validity of the AEOI for deployers of HRAIS, these obligations may also be relevant for companies outside the EU, even if the provider is not located in the EU but the output of the HRAIS is used in the EU (see above). Whether and how well these obligations can and will be enforced against companies in Switzerland, for example, is another question. As in the case of the GDPR, this is unlikely to happen, as there are also legal barriers in Swiss law that stand in the way. On the other hand, it should not be possible to impose vicarious sanctions against the representative acting correctly.

- Regulations for AI models

It was only late in the legislative process that the AEOI was expanded to include regulations for providers of certain AI models (the role of the deployer does not exist here). However, only models that can be used for a wide variety of purposes (“general purpose”) are covered (GPAIM). However, it is not clear exactly how these differ from other models. For example, it could be argued that a transcription-only model such as “Whisper” or one for translations only is not a GPAIM. However, if a GPAIM is “specialized” in certain topics such as legal issues through fine-tuning, it will probably continue to be considered a GPAIM because it can still be used for many different applications.

It is apparent from the recitals that GPAIM are not only recorded in their original form, i.e. as files, but also where they are offered via an API (application programming interface) as a kind of ‘model-as-a-service’. According to the considerations, they are also not considered AIS, i.e. the corresponding obligations are also ineffective because they lack a user interface (why an API should not be considered as such is not explained). Thus, if OpenAI offers access to GPT4 via an API in addition to “ChatGPT”, it does not have to comply with the AIA requirements for AIS within the framework of this API, while “ChatGPT” is considered AIS and the specifications must be observed. The requirements for AIS are then subject to the person who uses the model in his application (insofar as it is considered AIS); he then becomes their provider because he has developed the application and he uses it for himself. However, if he brings this application to the EU market or uses it in his own company, the model placed on the EU market also applies.

Anyone who creates a GPAIM but only uses it internally is not covered by the requirements for GPAIM because he is only considered a provider if he would bring the GPAIM to the market; the criterion of “putting into service” only applies to AIS, probably due to a legislative oversight. According to the recitals, the exceptions should have been narrower.

In particular, GPAIM providers have the following obligations:

- They must maintain and update detailed technical documentation of the model for the attention of the supervisory authorities.

- They have to keep and update a much less detailed documentation of the model for the attention of the users of the GPAIM.

- If they are outside the EU, they must appoint a representative in the EU.

- They must put in place internal rules to comply with EU copyright law, including its so-called Text and Data Mining (“TDM”) regulation and its right to opt-out. The TDM regime allows third parties to extract and use content from databases to which they have lawful access, but gives the holders of the rights to the works contained therein an “opt-out” right. Regardless of the AEOI, it is not entirely clear what the TDM regulation means for training AI models. With the new provision of the AEOI, it will be even more difficult to train AI models, because anyone who wants to offer a GPAIM in the EU later on must comply with EU copyright law when training their model, even if it is not subject to this right at all. The aim is to prevent a US provider, for example, from setting up its model under less strict foreign law and then launching it on the market in the EU. In other words, EU copyright law is effectively given worldwide validity for the purposes of GPAIM, since most of GPAIM’s providers also want to offer it in the EU.

- They must publicly state in summary form what content they have used to train their models.

Although the AEOI releases GPAIM from the first three obligations under a free, open license, it does not release it from the last two. In addition, the term “open source” is interpreted narrowly.

For providers of GPAIM that entail “systemic risks”, additional requirements apply. From the legislator’s point of view, a GPAIM entails systemic risks if it is particularly powerful, which in turn is measured by the computing power used to create it. The large LLMs, such as OpenAI’s GPT4, are therefore readily considered to be GPAIMS with systemic risks. However, the AEOI is openly formulated; other GPAIMS can also be declared to be GPAIM with systemic risks. Their providers must then also evaluate their models with regard to the associated risks, take appropriate measures to deal with the risks and collect, document and report serious incidents to the supervisory authorities, including the possible measures in this regard. They shall also ensure that GPAIM has adequate cybersecurity.

- Further Obligations for Providers and Deployers

The AEOI also defines some case-specific transparency obligations that should apply to all AIS, including those that are not HRAIS. In particular, it introduces obligations to tag and label certain AI-generated content.

Providers must ensure that:

- Persons who interact with an AIS are informed of this fact, unless this is obvious from the point of view of a reasonable user.

- the text, sound, video, and image content generated by an AIS is marked as AI-generated or AI-manipulated. This marking must be machine-readable. It is not yet clear how such markings should be done on textual content (while it is much easier to “watermark” images accordingly). Offering appropriate “AI content detectors” is not mandatory, but they will certainly soon be offered to identify such watermarks, which will hopefully be more reliable than what is on the market today. Since the legislator was apparently aware of the fact that its definition of AIS is very broad, it formulated an exception for AIS, which only support “normal” editing of content, provided that these tools do not significantly change the content. Providers of automatic translation services such as “DeepL” will try to take advantage of this exemption; they are entirely based on generative AI.

Deployers must ensure that:

- data subjects are informed when they are used in these AISs to recognise emotions or intentions or to classify them on the basis of biometric characteristics, and personal data is processed in the process.

- “deep fakes” generated by them are recognizable as such; however, there is an exception for creative professionals: if deep fakes are obviously part of art, literature, satire and the like, the reference may be restricted in such a way that the presentation and enjoyment of the work is not impaired. It will be interesting to see to what extent this exception is also applied to advertising.

- in published texts that concern topics of public interest, it is pointed out that these have been AI-generated or manipulated – unless the text has been reviewed by a human and a human or legal entity has assumed editorial responsibility for its publication.

The above obligations apply only to AIS, not to GPAIM. So if OpenAI offers an AIS like ChatGPT, then it has to make sure that AI content is marked as such in a machine-readable way. If it offers access to its models via API, it does not have to do so. The obligation then lies with the company that uses this API in its own application and thus becomes an AIS – if this company is considered a provider within the meaning of the AEOI and falls within its scope because it launches or uses its AIS in the EU.

If an AIS does not fall under these provisions, is not an HRAIS and is not a prohibited practice, then there are generally no obligations under the AEOI for providers, deployers and the other bodies involved with regard to the operation of this AIS. However, the AEOI generally encourages them to voluntarily adhere to codes of conduct that are to be developed in the field of AIS in order to ensure ethical principles, a careful approach to the environment, media literacy in dealing with AI, diversity and inclusion, and the avoidance of negative impacts on vulnerable people. Furthermore, an article that was only inserted in the course of the consultations provides for a kind of AI training obligation for providers and deployers, i.e. they must do their best to ensure that the persons who deal with AIS are adequately trained in it, are informed about the applicable obligations under the AEOI and that the persons are aware of the opportunities and risks of AIS (“AI literacy”).

Thus, for one or the other, the AEOI probably goes surprisingly little far in regulating the use of AIS, which are neither an HRAIS nor a prohibited practice – i.e. in the majority of cases in practice. This is despite the fact that numerous international initiatives, declarations and even the draft of the Council of Europe’s AI Convention have repeatedly formulated guidelines that have been identified as important for the responsible use of AI, such as the principles of transparency, non-discrimination, self-determination, fairness, harm prevention, robustness and reliability of AIS, explainability of AI and human oversight (see as well as our 11 principles). With the exception of selected aspects of transparency, the AEOI requires compliance with them only in the area of HRAIS, and even there not really consistently and primarily from providers; it does not, as shown, even allow the processing of special categories of personal data in order to test a “normal” AIS for bias and eliminate it (especially since the AEOI does not require this either). It remains to be seen whether the enforcement of these principles will take place in other ways (e.g. through data protection or unfair competition law), through guidelines that organisations voluntarily impose on themselves, or not at all.

- Application Examples

In the following, we have listed some practical application examples to show to whom which provisions of the AEOI can be applied in everyday life:

Case | Providers within the scope of the AEOI* | Deployer within the scope of the AEOI* |

A company in the EU provides employees with ChatGPT or Copilot. They use it to create emails, lectures, blog posts, summaries, translations, and other texts, as well as generate images. | No | Yes |

The company is located in Switzerland. It is planned that people in the EU will also receive the AI-generated content (e.g. as e-mails or texts on the website). | No | Yes |

A company in the EU has developed a proprietary chat tool based on an LLM and uses it internally to create emails, lectures, blog posts, summaries, translations, and other texts, as well as generate images. | Yes | Yes |

The company is located in Switzerland. It is planned that people in the EU will also receive the AI-generated content (e.g. as e-mails or texts on the website). | (Yes)1) | Yes |

A company in the EU uses a specialist application offered on the market for the automatic pre-selection of online job applications. | No | Yes, HRAIS |

A company in the EU uses ChatGPT or Copilot to analyze job applicants’ documents for any issues. The results remain internal. | Yes2), HRAIS | Yes, HRAIS |

The company is located in Switzerland and it is only about jobs in Switzerland, with applicants from the EU also being considered. | No | No3) |

A company in the EU provides a self-created chatbot on its website to answer general inquiries about the company. | Yes | Yes |

The company is located in Switzerland. The website is also aimed at people in the EU. | Yes1)4) | Yes |

A company in the EU uses a third-party product or service to implement the chatbot on its website. The company’s content is made available to the customer in the form of a database (RAG). The company does not specify who the chatbot is from. | (No)5) | Yes |

The company states on the website who the chatbot is from. | No | Yes |

A company in the EU uses an LLM locally to transcribe texts. The Python script to use it transfers it unchanged from a free template from the Internet to your own computer. | (No)6) | Yes |

A company in the EU uses a service from a US service provider that is also offered to customers in the EU to generate avatars for training videos. | No | Yes |

Remarks:

- The wording of the definitions argues against a qualification as a provider, but the legislator wanted to cover the company in this case as a provider to which the AEOI applies.

- This is where the special rule comes into play, according to which an AIS is used in such a way that it becomes an HRAIS; in this case, the user becomes the provider.

- There is no use of the outputs of AI in the EU, as we are talking about jobs in Switzerland; the nationality or origin of the job applicants must rightly not play a role, at least as long as the outputs of the AI are not sent to them, as in this case.

- The chatbot is an AIS that is also intended to be used by people who are in the EU. This means that the AIS is also used in the EU or is made available for this purpose.

- The parameterization, connection of a database and the integration of the AIS into the website should rightly not yet be considered a development; however, the legal situation is not yet clear.

- It can be argued that the adoption of the script is tantamount to the installation of a software that has already been developed and therefore does not constitute development; moreover, the company will not implement it under its own name. If the script is changed, the qualification might be different.

*The examples are to be understood as a generalized, simplified illustration of the concept, i.e. in the specific individual case, the assessment may be different.

- Enforcement

To enforce its requirements, the AEOI uses various authorities at the level of the individual member states and the EU. For example, GPAIM will be supervised by the European Commission, while AIS will be supervised by the Member States. Again, a distinction is made between the system of conformity assessments and declarations and the actual market surveillance. The system is further complicated by the fact that where market supervision already exists (for regulated products and the financial industry), supervision is to continue to be carried out by the existing authorities. If, in turn, an AIS is based on a GPAIM from the same provider (e.g. ChatGPT), the newly created, central “AI Office” is responsible for market supervision. If, in turn, such an AIS is used in such a way that it must be considered as an HRAIS, the national market surveillance authorities are responsible.

The AEOI grants the market surveillance authorities far-reaching powers of investigation and intervention. This goes so far that it can also demand the release of the source code from AIS. In any event, they must investigate an AIS if they have reason to believe that there is a risk to the health, safety or fundamental rights of the persons concerned or if an AIS is wrongly not classified as HRAIS. Formal violations (lack of declaration, etc.) must also be prosecuted, and of course any data subject in the EU can report a violation of the AEOI to them.

By their very nature, national market surveillance authorities are confined to their own territory. It is unclear what responsibilities they have with regard to providers and deployers in EU third countries such as Switzerland and the USA. If the market surveillance authorities of the individual member states get into a clinch with each other with regard to the measures to be taken, the European Commission decides.

Of course, the AEOI also provides for administrative fines. As under the GDPR, they are supposed to be “effective, proportionate and dissuasive“. Overall, the range of penalties seems somewhat milder than that of the GDPR. Only the penalty range for prohibited AI practices goes significantly higher at 7% of global annual turnover or, if higher, EUR 35 million. Otherwise, it is a maximum of 3% or EUR 15 million or even lower in certain cases. In contrast to the GDPR, it is emphasized that they should take into account the interests of SMEs, including start-ups, which is shown, among other things, by the fact that the penalty range for them is to be determined at the lower value when it comes to AIS. As under the GDPR, the negligent violation of the AEOI can and should also be fined.

- Transitional provisions

The AEOI enters into force on the 20th day following its publication in the Official Journal. However, its regulations do not apply until 24 months later, with the following exceptions:

- The banned AI practices are banned after just six months;

- The regulations on GPAIM and the bodies that can issue declarations of conformity will apply after twelve months;

- The regulations on HRAIS due to existing EU product regulations will only apply after 36 months.

As part of the “AI Pact”, the European Commission has called on industry to implement the AEOI in advance.

From a transitional point of view, there is no exception to prohibited AI practices that existed at the time of the entry into force of the AEOI.

For HRAIS that were already placed on the market before the AEOI, the new regulations will only apply if and only if they are significantly adapted. For GPAIM that were already placed on the market before the AEOI, the requirements of the AEOI must be met within two years of the entry into force of the respective rules.

- Concluding remarks and recommendations for action

It remains to be seen whether the AI Act will live up to the high expectations placed on this AI regulation. The decree gives the impression that the legislature has tried to position an arsenal of defensive means against an enemy that it does not really know yet and of which it does not know whether and how it will strike with what effect.

It is emphasized that the AI Act is designed to be risk-based. This does indeed seem to be the case, at least considering that the regulation of the use of “normal” AI applications remains (perhaps surprisingly) very tame, with very few and specific “hard” provisions. However, when it comes to the applications that are considered particularly risky, there is a lot to draw on and a lot is expected of the providers – and some things for which there are no recognized “best practices” yet, for example in the area of dealing with data for AI models. Fortunately, these high-risk applications are comparatively narrow and, above all, conclusively defined, even if the list can be adjusted over time. After all, providers of products that are already regulated and in the field of critical infrastructures will have to deal with them particularly intensively.

For most companies in the EU and to a lesser extent in Switzerland, the AI Act will bring work, but it should not get out of hand if they have a reasonable handle on where AIS is used in-house in their own products and services and those used by third parties. Above all, they will want to ensure that they do not fall into the “minefields” of prohibited or particularly risky AI applications. However, if they stay away from it, they should be able to cope with the few remaining obligations (mainly for transparency) comparatively easily, even if they are considered “providers” because they have developed or further developed an application themselves. An exception may be the obligation to tag AI-generated content; there is currently a lack of suitable standards and ready-to-use solutions. It will be interesting to see what the market leaders will offer here, especially for AI-generated texts.

Swiss companies will also not be able to avoid the AI Act, even if it only applies to them to a limited extent and, as in the case of the GDPR, it cannot be assumed that they will be in the focus of the EU supervisory authorities. Admittedly, it is not yet clear in all cases whether the AI Act will apply to them because mistakes have been made in its formulation. However, it must be expected that the use of AIS is covered if the output is intended for recipients in the EU or is otherwise used in the EU. If a Swiss company offers its customers in the EU market AI functions under its own name as part of its products, services or website, which it has developed at least in part itself, it is also covered. However, as long as it is not a high-risk application, the obligations are again moderate.

As a result, for most companies, the main effort will be to understand what AI is being used in their own company and in what form, in order to be able to react in time if a project moves in the direction of one of the aforementioned minefields. When it comes to a high-risk application, companies will be well advised to avoid the role of the provider and therefore in-house developments, because the provider has disproportionately more obligations than the pure deployer.

This leads to our recommendation for action: Companies should record all their own and third-party AI applications and assess according to whether and in what role (provider, deployer, distributor, etc.) they will fall under the AI Act. Once this has been done, appropriate requirements must be issued to ensure that these AI applications are not used without prior examination in a way that leads to a different qualification. On the other hand, in cases where the AI Act applies, the resulting obligations must be identified and a plan drawn up on how to implement them within the prescribed deadlines. This recommendation applies analogously to new projects.

By Vischer, Switzerland, a Transatlantic Law International Affiliated Firm.

For further information or for any assistance please contact switzerland@transatlanticlaw.com

Disclaimer: Transatlantic Law International Limited is a UK registered limited liability company providing international business and legal solutions through its own resources and the expertise of over 105 affiliated independent law firms in over 95 countries worldwide. This article is for background information only and provided in the context of the applicable law when published and does not constitute legal advice and cannot be relied on as such for any matter. Legal advice may be provided subject to the retention of Transatlantic Law International Limited’s services and its governing terms and conditions of service. Transatlantic Law International Limited, based at 84 Brook Street, London W1K 5EH, United Kingdom, is registered with Companies House, Reg Nr. 361484, with its registered address at 83 Cambridge Street, London SW1V 4PS, United Kingdom.